Did I mention how awesome it is to live 30 minutes from a ski lift?

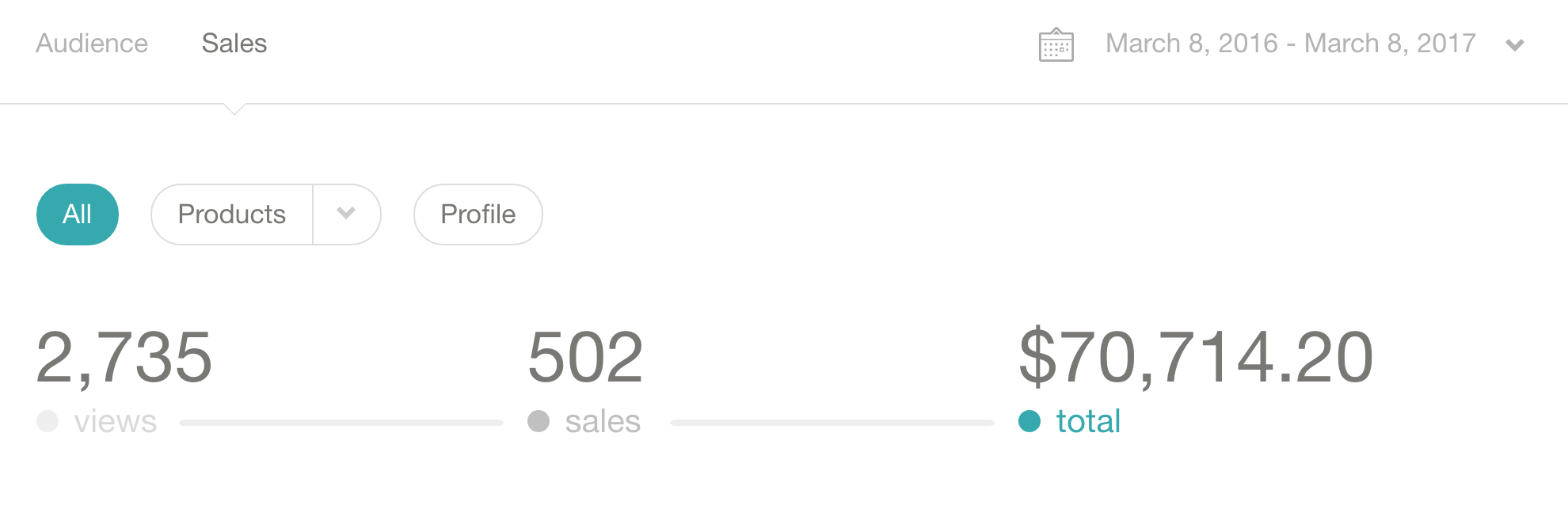

In March of 2016, I launched a course called The Complete Guide to Rails Performance. Since then, I have sold just over 500 copies, for gross revenue of $131,521.20 ($1050/week). Although I launched the course in March, I had worked on it for about 4 months. Releasing the course has been a lifechanging event for me. For the first time ever, I made more money over a year from product revenue rather than service revenue. Releasing the course nearly doubled my usual freelancing rate, allowed me to change my lifestyle by moving to a ski resort town in New Mexico, and turned me into something of a minor Thought Leader ™ in the Ruby on Rails field.

In this post, I’d like to share my process for creating The Complete Guide to Rails Performance (henceforth “the CGRP”), what I’d do differently in the future, and how creating a programming information product radically changed my freelance career.

It would be immensely helpful to me if other programming authors (self-published or not) would email me to share their own experiences and results. I’m not sure if I’m an outlier or just the average case!

The Path to Making Money While You Sleep

I ain’t programmin’ here no mo’!

I was on the first season of ABC’s Shark Tank when I was only 18 years old.

I think “product money” is the eventual goal for nearly all freelancers or solopreneurs. There’s probably a lot of developers sitting on the sidelines too wishing they could tell their boss to take this scrum and shove it. And, now that I’ve made some product money, I can tell you it is pretty awesome. Waking up with more money than you went to bed with is a very, very good feeling. I’ve been trying to “start a business” since 2008 (you may know me from my appearance on ABC’s reality show Shark Tank in 2009). It’s always been a struggle for me to find the magical intersection in the theoretical Venn diagram of my interests/skills and what people will pay for. For some reason, I had always avoided information products, because all I knew about was programming, and specifically Ruby on Rails. I think I wanted to get out of programming, and make a product for more “normal people”, like the infamous Bingo Card Creator.

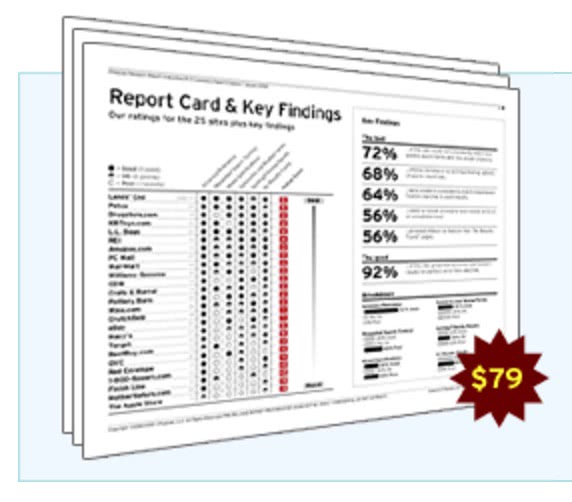

The copy bragged that it was ‘featured on InternetRetailer.com!’

For some reason, as software developer solopreneurs, a lot of us are caught up on SaaS products. Yes, subscription revenue is great. But SaaS is not easy, and the effort of creating one frequently means you’re sinking tons of your own development time into something that doesn’t end up making any money (or doesn’t make enough to compare with your freelancing rate). Worse, as developers, we love coding. In fact, a lot of us love it so much that we can code for years without actually shipping anything! It took me a long time to get past this. In the end, something from Amy Hoy actually pushed me over the edge – she pointed out the 37signal’s first product wasn’t a piece of software, it was an information product. It was a ~$79 45-page whitepaper about SEO. You can still download it here. But, of course, it was dripping with the viewpoint, style, and contrarianism that we’ve come to expect from Basecamp-nee-37signals. All that was important, all that made 37signals what it is, could still be delivered in a simple information product rather than a SaaS.

That was the last push I needed – I was firmly thinking about creating an information product for programmers. This was in May of 2015.

The original tweet from when I launched

In all, it took about 9 months from being a normal, run-of-the-mill Rails freelancer to launching the course. It took about 4-5 months to actually create the product itself, though in retrospect I could have compressed it to about 3 months if I had better daily writing habits. In all, about 240 hours went into the production of the course, and I would estimate another 60 hours of work went into it post-launch (as I released/recorded the video content, which I’ll get into later). For those of you doing the math at home, that’s an hourly rate of $291.

I’m going to break down the steps I took to create the course into 5 parts:

In tech, early majority means ‘someone is using this to make money.’

- Choose a subject and audience – choose a subject area which is in the early-to-late majority, is something you have deep knowledge about, and something you can take a contrarian or novel position on.

- Find your voice – this is your “brand”. Look at the current writing in your chosen subject area, and then try to do the opposite.

- Blog posts as prototypes – Hone your subject, audience and message by treating blog posts as product prototypes. Measure engagement and use it to refine your writing and message.

- Build your following – Continue to crank out content on a regular basis. Build an email newsletter and social following.

- Build the product – While writing your posts, slowly build your product. Create some add-ins (videos, Slack channel, interviews), and distribute via your newsletter and Gumroad.

Finding your Subject Area and Audience

If you thought a programming language couldn’t be worse than Brainfuck, you were wrong.

Spoiler alert – you can’t just write about whatever you want. This guide isn’t going to be about how you can become a successful author by writing in-depth tutorials about . The first step is taking a guess at where your expertise and what people want intersects. This is often the hardest part for most, but if you can nail this (and finding your unique voice, in the next section), the other sections are much easier.

I’m a Rubyist. I’ve been programming in Ruby since about 2011, so I knew whatever I did had to be Ruby-related. My actual work experience with Ruby was entirely with small startups and companies – my first few jobs I was the the only full time engineer, and my freelance work has almost exclusively been for small startups, usually just out of YC or 500Startups.

POODR represented the majority of Ruby/Rails writing at the time. It was a great book, but the field was oversaturated.

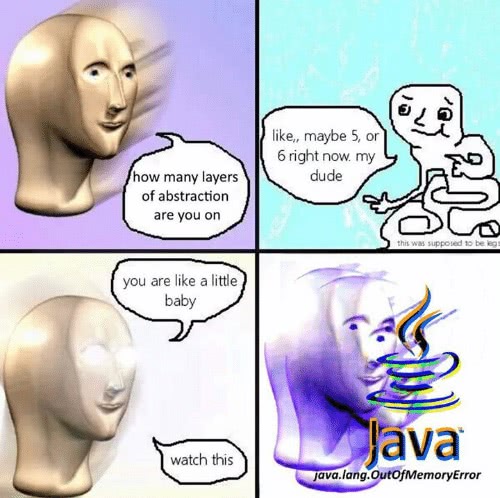

So – I knew Ruby (and Rails), and I knew startups. Most writing in the Ruby/Rails field up until 2015 had primarily been around “maintainability” anxiety, especially after the release of Rails 3. Most Ruby authors touted the benefits of taking a more Object-Oriented approach to Rails applications. I would consider the leaders in this category to be Sandi Metz (Practical Object-Oriented Design in Ruby), Avdi Grimm (Confident Ruby), and Russ Olsen (Eloquent Ruby). So, that area of Ruby writing was generally pretty well taken care of. Also, I didn’t much care for some of the rhetoric of some of these authors (“maintainability” being a very slippery justification for endless layers of abstraction, such as “Hexagonal Architecture”), and thought their writing didn’t adequately address all of the everyday problems of small Ruby shops like I was used to working with.

Of course, there was a lot of “how-to” content in Ruby as well by 2015. The Pragprog book was the defacto standard, but Michael Hartl’s Rails Tutorial and _why’s legendary Poignant Guide also were valuable for beginners. Advanced users had the excellent RubyTapas screencast series. With the immense competition in this subcategory, I didn’t think I had anything I could add there either.

But in 2015, a new zeitgeist was taking hold in the Ruby community. Rubyists had always had anxiety about the performance of their applications, but it was reaching epidemic proportions. JavaScript and Node had long been attempting to steal Rails’ de-facto leading position on the server, but now even more languages, such as Rust, Go, Scala and more were trying to usurp the king. Ruby-like languages (Elixir, Crystal) had started to pop up as well, promising the friendliness of Ruby with greater performance. Rubyists were (and still are) deathly worried that they were being left behind by faster languages. It was visible in the blog posts and conference talks – Rubyists were considering jumping ship for “faster” languages.

I’m good, thanks. via twitter

Surprisingly, Ruby-specific performance writing was pretty darn thin on the ground at the time. For a community that looked longingly through the window at faster languages all the time, no one seemed to be able to tell you how to make your existing Ruby application faster. The prevailing advice was “rm -rf and rewrite it in JavaScript”, or a compromise position of “use Rails as an API, use a single-page-app framework on the frontend”.

So there was the landscape:

Pictured: someone’s Webpack config file.

- I loved Rails and had deep experience in Ruby and Rails web applications.

- Rubyists had a lot of anxiety about speed and performance, which was extremely clear thanks to all the conferences talks about other languages popping up (Elixir for Rubyists, etc etc) and blog posts about how much faster X framework was.

- “How-to” content for Ruby was pretty much paved over at this point, as was “object-oriented-programming” themed content.

- I knew that small Ruby startups struggled with writing fast, performant applications, and didn’t want to completely throw away their existing applications and skills by switching languages or frameworks. They wanted the “get shit done” approach Rails was famous for, not the “learn these 4 frameworks and 12 build tools” approach JavaScript had adopted (a friendly jab!).

So, I had my subject area: Ruby performance. While this is how I arrived at my subject, here’s some things you should consider when trying to decide on your programming content’s subject area.

Pictured: Pat introducing C programming to a mostly-Ruby audience

You can introduce an old topic to a new audience. I’m sort of doing this (performance is an unusual topic for Rubyists, though not so in other language communities), but other authors do it more deliberately. You can take concepts from one language and teach it to another group that may not be familiar with it (“Functional Programming for Rubyists” for example). Pat Shaughnessy, a favorite author of mine, writes about the internals of Ruby’s C runtime for the everyday Ruby audience. The internals of a language runtime (and the C language!) are areas Rubyists know little about, but this knowledge is useful because it can explain some of Ruby’s quirks and characteristics.

What businesses do when you solve their needs.

Your subject area should ideally be an expensive problem for businesses. It is extremely difficult to make money from an audience that perceives your writing as a hobby or side-project – you need to sell them something they need rather than something they want. Most “how-to” or “learn X language” falls into this trap. Far better to look at the sort of problems your audience has and try to solve them. For example, in the Ruby community, authors that write about “object oriented programming” frequently sell their content in terms of reducing maintenance and refactoring costs. “Agile programming” authors typically make their case in terms of increasing feature velocity and increasing a project’s resilience to requirements changes. And, of course, in my subject area, performance improves customer experiences and reduces scaling costs.

A major trap to avoid in programming writing is what I’ll call the “StackOverflow trap”. A lot of programmer blogs (mostly the beginner ones), read like a series of StackOverflow answers. They’re short posts that describe a solution to a narrow, specific problem encountered in the programmer’s day-to-day work. I guess if you wrote a thousand of these you might have some kind of astroturfing/SEO strategy, but it’s not the kind of content that keeps people subscribed and coming back.

Your subject area and audience should be something you know deeply, not just something you’ve picked up in the last 6 months. Don’t write about a language you just picked up a few months ago and only use on the weekends, for example. You’ll have more success deeply specializing in a popular category. It’s generally easier to pick up a new specialization rather than learning an entirely new skill. I actually didn’t know all that much about performance before I started writing about it, but I knew quite a lot about Ruby and Rubyists, since I had been one for 4 years prior to getting started.

While you should look to stand out with your positioning and your writing voice (I’ll get to those in a minute), you shouldn’t look to be too unique with your subject area. Many languages just aren’t big enough yet to support a major book or information product about them – far better to pick a mature language and introduce a new concept to the users of that language.

So, I knew what I was selling (content about Ruby performance), but now how would I sell it? What’s my “angle”? That’s the question of positioning.

One way to get people’s attention is to make a good, reasoned argument in favor of an unpopular position. This seems counterintuitive – surely, if you wanted a larger audience, you would pick the popular position, right? However, the popular position probably has dozens of people already writing about it (that’s how it became popular in the first place), and you’ll have to work twice as hard to stand out. It’s better (and easier for you) if you can look at your own programming opinions, find the unpopular, uncommon or weird ones, and then write about those. Hacker News loves a good controversy or devil’s advocate, and if you can eloquently take the “con” side against a 200+ point front-page post, you can pretty much guarantee yourself a front-page post of your own when you post your counter-argument. More on distribution channels later though.

Here were the unpopular positions I held (and still hold) which helped make my blog more popular:

It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.

- I believe in Turbolinks (Rails’ oft-reviled JS plugin) and am opposed to JavaScript frameworks for most applications. This position was what lead to some of my original exposure – I first gave a talk about why I thought Turbolinks was underrated at GORUCO in 2015, which was very well received. A few months after the talk, I published a blog post about Turbolinks which received tens of thousands of visits after being shared by DHH on Twitter.

- I think Ruby is “Fast Enough”. I think that if an application server can reliably serve a response in 100ms or less, then horizontal scaling will take care of the rest and we can just throw more hardware at the problem. Thankfully, with a little knowledge and optimization, any Ruby or Rails application can meet that threshold. Programmers like looking at “relative” benchmarks – such and such framework is 100x faster than this other framework, for example. But, if we’re talking about the app servers responding in 100 milliseconds or 1 millisecond, I think the difference is only in your server bills.

- Frontend performance is just as important, if not more important, than backend performance. Frontend performance – rendering times – are by far the largest contributor to end-user perceptions of performance. Application servers respond in ~100 milliseconds, but front-ends routinely take 3-5 seconds to load. Rails developers frequently have “full-stack” responsibilities but rarely know anything (or care) about front-end performance, but I think that’s a mistake.

- Scale doesn’t mean Twitter scale.

Most writing about “scaling” turns into an ego-measurement contest where “real scale” only starts at 1,000 requests per second. The reality is that I’ve seen tons of applications fail at scaling to 100 requests per minute, because the engineers running it don’t understand the basics of how many servers they need for how much traffic, or they’re kneecapping their application’s performance through a few simple settings that they never bothered to tweak. So when I write about “scale”, I mean dealing with an increase in traffic, not some arbitrary requests-per-second number that internet commenters think is “Real Scale”. - I respect my audience’s privacy and freedom. The pages on my blog weigh about 10 kilobytes in an era where most publisher’s websites weigh nearly 10 megabytes. I send emails to my newsletter in plaintext, and I don’t track clicks. All of my content is secured with HTTPS/TLS. I don’t use trackers anymore – I recently removed Google Analytics from my site when I realized it didn’t really matter to me. My course (detailed later) did not have any form of DRM, and I even shipped the “source code” (markdown files) to my purchasers. In a technically savvy audience, like mine, people notice this sort of thing, and they respect you for it.

- I write in-depth, lengthy content. In an age of 10-second viral videos and 140-character discourse, my content is frequently 4000-5000 words, the length of a magazine “long-read”.

Those are just my positions. If you’re considering writing about programming yourself, here are some positions that others have taken or that you should consider:

- Look at the dominant groupthink, and head the opposite way.

Unpopular opinion: everyone who hated this does not understand why Rails succeeded. There seems to be a lot of opportunities here in JavaScript, for example, which is a community with extremely strong groupthink. Who’s advocating for simplicity in JavaScript? As far as I can tell right now, no one. The bigger and badder the framework, the better. What about stability in JavaScript? Right now, it’s a matter of learning the hot new framework of the month. Someone that wrote about using vanilla, no-framework JavaScript in a practical setting or wrote about simpler, smaller libraries would probably do really well in this climate, I think. Maybe this already exists, I’m not a big follower of the JavaScript blogosphere. Or with programming languages in general, the meme right now is in favor of strongly typed languages – well where’s the classic OO, dynamic-typing advocate? Who’s reviving Alan Kay or some of the genius of the original Smalltalk? Look at the well-travelled road, and head the opposite way. No subject area in programming can support only a single, correct position. There’s always an alternative, and those alternatives need advocates.

Finding Your Voice

Your voice is the “who” of writing – what about your content makes you different from everyone else? This is what technical publishers, such as PragProg or O’Reilly, typically get very wrong, in my opinion. Pretty much every published programming book sounds exactly the same, like it could have all been written by the same person. In some sense, it is, because it’s generally all reviewed by a small cadre of editors. To stand out, you need to not do that.

My favorite example of this (from the Ruby community, of course) is Why’s Poignant Guide to Ruby. If you’re a Rubyist, you already know what this is, but if you’re not, it’s a legendary tome in the Ruby community. Full of lengthy tangents, comic strips, and nonsensical examples, it reads a bit like a programming how-to book written by Alejandro Jodorowsky. But that’s not really doing the Poignant Guide justice, because it really reads like it was written by _why. I don’t think anyone’s written any programming book like it before or since.

Having a unique voice is one of the most important things you can do to make your content stand out in a sea of “blah”. It’s what will make readers remember you and keep coming back.

No rules, just Hemingway shooting the cameraman in the face.

“Having a unique voice” means there are no rules. Some advice that I’ve heard given out a lot is to improve the quality of your writing by reading Strunk & White, George Orwell, or other books about the craft of writing. However, perfectly crafted sentences with beautiful alliteration, structure and word choice is just one possible voice in a sea of possible voices. More important than crafting your sentence like Hemingway is sounding different than everyone else in your field. Correctness of spelling and grammar is really only relevant up to a high school English level – everything beyond that is just extra credit. Your audience must be able to understand you, but they don’t need to think you’re Hemingway. My posts are often riddled with spelling errors, for example (and I think I’m a good speller!). At the same time, though, overly friendly millennial copy is greatly overplayed. Not every sentence needs to end with a meme.

Look at what others are writing in your subject area, and do the opposite of that. In most technical writing, and particularly in my field, performance, the author is overly dry, formal, and typically assumes a knowledge and competence far beyond that of the average reader. Almost all technical writing could benefit from an injection of creativity, humor, the weird, the wild. Most performance writing was targeted to the top 1% of programmers in the field, but all of us deal with performance on a daily basis.

I decided to take a different tack and write for the other 99%, clearly explaining terms when I used them and linking to more information if someone wasn’t familiar with what I was talking about.

By the way, if any of you steal my sidebar GIF shtick, I’ll beat you up. The sidebar of my blog contains a running commentary of GIFs. I swear a lot. It’s definitely not the sort of thing you’d get by picking up the latest O’Reilly book.

Everyone is interesting in some unique way – finding your voice is just a matter of taking that interesting stuff and turning it up to 11.

Yeah, Aaron’s unique alright. Aaron Patterson, Ruby and Rails core member, is a good example of a programmer with a unique voice. His conference talks (which are always packed, because everyone knows what to expect) are hilarious, pun-filled affairs which always end up getting deep into the technical weeds of Ruby or Rails’ internals. The humor in Aaron’s blogs and talks is the sugar that helps the technical material go down. Humor isn’t the only way to stand out, though – you might say an author like Zed Shaw or Gary Bernhardt has more of an “angry” voice. “Voices” don’t even necessarily have to do with the writing: Bret Victor, for example, is known for his excellent charts, graphs and typography.

Think of your writing voice as the exaggerated, caricature version of yourself. Look back at presentations you’ve given or things you’ve written in the past, and think about what’s been interesting for others. What have people told you they enjoyed about them? I have a minor reputation for a somewhat frantic, energetic presentation style. I carried that back into my writing by mimicking how I speak – energetic, sometimes tangential, and usually funny (at least to me).

‘Modern writing consists in gumming together long strips of words which have already been set in order by someone else, and making the results presentable by sheer humbug.’ – George Orwell

Whatever you decide to go with, remember that the only good position in writing is a confident, strongly held one. People want to hear about strong opinions, not me-toos or “gee I dunno”. This may mean that you need to carry out more research before writing, so that you can gather more evidence and be completely certain about your conclusions. Or, it may mean that you need to remove filler phrases that soften your sentences, such as “I think” or “I suppose”.

Posts as Prototypes

Now that you’ve got a hypothesis of what you’d like to write about (your subject area) and how you’ll write about it (your voice), you need to start writing.

‘Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout with some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand.’ – George Orwell. He was a smart dude, obviously.

This is the hardest part. If you were hoping for some kind of deep, dark secret that writers use to get stuff on the page, then you’ll be disappointed to learn that there isn’t one. It’s painful. I still find the actual act of sitting down and writing extremely difficult. It gets slightly easier, but not by much. I don’t know of many professional writers who describe the writing process as “fun” – it’s a battle, a daily battle.

There are many resources, though, for dealing with this daily battle from those who’ve come before. The Artist’s Way is a popular book for learning how to build a writing habit, though I found The War of Art more to my own liking. Everyone will tell you the same thing, however – write every day, no matter what. Building a writing habit is really about learning to separate the task of writing from editing. Writing is about just getting anything down on the page. It doesn’t have to be good, interesting, or even coherent. Editing, the thing we do after, not during writing, is where we actually make the good stuff come out of our writing. Learning to separate these tasks, which rely on completely different modes of thinking, is the best cure for writer’s block I’ve found yet.

You need to put your writing somewhere online, of course. Since this post is about writing for programmers, you’ve got quite a few options. I use a custom Jekyll site and theme, which is hosted on Amazon S3 using Cloudfront as a CDN. Jekyll on Github Pages is also popular, although recent changes to their Pages product means that this is no longer an option for high-traffic blogs.

No, a micro AWS instance is not a good idea.

If you’re not going to use a hosted solution, such as Medium, you must must must have a static site hosted on a big-box provider (such as Amazon) and use a CDN. So many personal programmer blogs are hosted on two-bit VPSes, which are more expensive than Amazon S3 and always fail when the site frontpages on HN. I intentionally designed my own blog so that I don’t control any of the servers that host my site, and it has never gone down or even slowed during periods of high traffic. Hitting top-10 on HN or getting a massively retweeted post is a critical moment for any website, and you cannot afford to go down during those times. Do not run your own servers, let someone else do it for you.

Don’t overload your site with marketing flim-flam. You’re writing for a savvy technical audience – nerds that still use outdated technologies such as lynx, browsers which respect privacy rights, and RSS for example. My latest redesign of my blog (the speedshop one, not this one) doesn’t load a single thing which is blocked by content blockers such as uBlock Origin. People notice. I don’t load Google Analytics because I’ve realized the numbers are just vanity metrics that don’t change how, when or what I write about. I even write my email newsletter in plain-text now.

Don’t overload on metrics. Of course, you need to have a few key numbers in order to measure the uptake of your posts, but you don’t need Optimizely and a thousand other analytics widgets. My key numbers, for example, are social shares and newsletter signups.

Distribution

OK, you’re writing a great post every couple of weeks or so, now how do let everyone know about it?

The easiest way to not be this guy is to actually have a great product.

First, let’s remember that a good product is the best marketing you can have. If after ~3 months of posting you’re still not getting the numbers you want, it means that your writing just isn’t hitting the right buttons. Either your subject area is too narrow, your positioning is uninteresting, or you haven’t cranked your voice to 11 yet.

The king of permission marketing, Seth Godin.

The entire strategy I followed is based around building permission. We are giving away awesome things for free (our blog posts, which are like miniature products) in return for the permission to market to someone in the future. I give you an awesome, informative blog post, and you give me your email address and the permission to email you in the future (your newsletter). So, with that in mind, our most important distribution channel is gonna be our newsletter.

There’s a lot of ways to embed a newsletter in your posts. I’ve waffled back and forth a lot on this, and ended up with a popup in the lower-right-hand corner that appears after you’ve scrolled halfway through a post, and an additional signup box at the end of the post.

My current newsletter side-popup. It never appears again if you click the X. A lot of people choose to go for the big, obtrusive popover for a newsletter signup. You know the kind – it completely blocks out the page content and says “sign up to get my 5 free tips about…” I don’t think this works for a technical audience that spends most of their day on the Internet. Maybe it even does work to juice the numbers on newsletter signups, but remember: if they put in their email address just to get your stupid popup to go away, they didn’t give you permission to market your product to you later. Newsletter signups are about capturing the permission generated by your great content, so you want them to be useful, not obtrusive. How can a reader possibly give you permission if they haven’t even read your content yet?

As for what you actually use to send your newsletter, it doesn’t matter. I use Mailchimp, but I think I only use about 10% of it’s available features. When I started, the only way you could sign up for my newsletter was to email me and I would add you to a spreadsheet. When I sent a newsletter, I just copied all the email addresses from the spreadsheet into Gmail.

I’ll also note here my success with plaintext newsletters. I’m not sure if it gets past spam filters better (or worse), but I got a lot of appreciative emails from my readers when I switched. Try it on your own list.

As for newsletter content, I usually just write it every time I write a new post. I write about a few hundred words about the post and include a link. Nothing fancier than that.

Your other main channel, the one you’ll use to get new readers, is social media. The exact social media channels you use are going to differ depending on your subject area. In addition, Medium, if you’re using that to publish, is sort of like a social network of it’s own.

Different social media sites do better for different content. Here are the social media channels I’ve had success with, and what kind of content tends to do better on each:

- Hacker News –

The granddaddy of them all. HN still drives more traffic than almost any other programming-related social media channel if you can get into the top 10. Admittedly, however, the top 10 can be difficult to achieve. I’ve never used tricks like voting rings, asking friends to upvote, or stuff like that. I think HN has gotten good enough at detecting that now that it isn’t worth it. What is important is picking a good time to post (9am to 5pm PST) and driving a lot of traffic to your post at once using your newsletter or other channels. Getting to the frontpage is a matter of momentum, so throwing all of the traffic you possibly can at a post at once tends to help. The kind of content that tends to do well on HN are contrarian thinkpieces and stuff about the latest/greatest programming memes (static typing, concurrency, whatever the latest hot topic is). - Reddit –

Typical reddit content, also known as a ‘dank meme’ I primarily post to the Ruby and webdev subreddits. My more “how-to” content tends to do better here. The programming subreddit is more of a Hacker News mirror. At best, Reddit will drive 1/10th of the traffic HN does for me, but it tends to be more targeted to the audience I want. - Twitter – The virality of a post on Twitter seems nearly impossible to predict, but it still provides a steady stream of traffic for me.

- Lobsters – A lesser-known Hacker-News-like site. Lobsters used to be more biased towards highly technical content and the typical HN “X Considered Dangerous” thinkpiece wouldn’t do well there, but that seems to have changed in the last year. While Lobsters still likes a good “how I implemented Unix using chewing gum and a CB radio” technical deep-dive, they’re now more like HN without the business content.

Building The Product

Once you’ve gotten several successful posts and about 1,000 newsletter subscribers, you can start thinking about creating a product.

The product development process I describe here is basically recycled Lean Startup methodology – nothing novel or special. If you’ve been following this guide so far, you’ll note that you’re already going through the old “build-measure-learn” cycle through your blog posts.

It’s important to realize this will be your first product, and certainly not your last. Most people in this for “the long term” will end up with a product ladder of several products of increasing complexity and price. A product ladder serves two purposes: price discrimination (to capture maximum value from those who can afford to pay you), and to build trust by starting customers unsure of your ability to deliver at lower levels of the ladder and slowly upselling them up the ladder.

There are a million ways to slice this, but my product ladder has five rungs:

- A free product.

This is my blog. Some people like to have some kind of downloadable whitepaper or other PDF product in this slot, but I think those feel kind of cheesy. So, for now, my blog occupies the “free” slot of my ladder. - A $10 product. In the “$” tiers, it’s important to realize we’re talking orders of magnitude here rather than exact prices. So my “$10” product may actually cost $5 or $15 or $20. I don’t have a $10 product yet, though I have a few ideas for one. I’ll try to deploy one this year. A $10 product is 99% of the time going to be a short e-book, or perhaps a screencast (or even a screencast series, where you pay $10 a month). I would not recommend starting your product ladder from this rung.

- A $100 product.

This is where you should aim to start your product ladder – a major information product somewhere between $100 and $500. My product, the Complete Guide to Rails Performance, comes in two packages – a $99 and $199 package, but 80% go for the $200 package. In retrospect, I probably could have even gone for $150 and $300, but the eternal curse of a newbie product creator is to undervalue their own output. Don’t forget that when pricing your own product. A $100 product can usually take the form of an extensive, specialized book plus some throw-in extras, like screencasts, interviews, and a private Slack channel. I say that you should start your ladder here because it’s a great way to build up cash – I sold only a few hundred units of this product and made nearly a full-time salary off of it. It’s much easier than selling thousands of $10 products, but you also don’t have to deliver as much value (read: do as much work!) as for a $1,000 product. You may think this price tier is way too high for a book and screencasts – I disagree, and I think the proof is in the pudding of my results. I offer highly specialized information you cannot get anywhere else. Following my recommendations can save you thousands of dollars in server bills. $200 is a steal. - A $1,000 product. This is where most product ladders start to blur between products and services. For me, this ladder of my rung is occupied by Speedshop Reports, where I produce a lengthy customized performance analysis of a client’s Ruby on Rails application, telling them where their performance problems and opportunities for improvement are. Some very complex information products can occupy this rung, but the amount of work required to deliver this amount of value means I wouldn’t recommend it for beginners. Take a look at Amy Hoy and Ramit Sethi’s stuff if you want to see what a $1,000-tier infoproduct looks like.

- A $10,000 product. This level of value is probably difficult to deliver without personalized service. For me, this is currently in-person workshops at large corporations.

Again, I recommend getting yourself in the mindset of a $100-tier (a $100-500 price point) information product. It’s a great balance between several concerns: capturing maximum value from your audience with a single product, it’s complex and delivers a lot of value but doesn’t take a year of effort to produce, and it provides plenty of revenue for you to use to fund the rest of your ladder.

In addition, I don’t recommend starting with a subscription. These seem far harder to sell nowadays because the competition is so steep – every freelancer thinks they want a subscription revenue stream, so there’s an endless sea of $10/month screencast services that you’ll have to compete against. The secret is that with a high-enough priced product (i.e. not a $10 product), you can make just as much money and experience similar stability as you can with a subscription.

As for actually deciding what my $100-tier product was going to be about and how I was going to sell it, I followed Brian Harris’ process almost to the letter. If you’re seriously following this post as a guide, I suggest just heading to him directly but the gist of it is:

Original splash image I used to test the CGRP

- Take 50 newsletter subscribers as a cohort and ask them to pre-order – Time for our first build-measure-learn loop! Take 50 newsletter subscribers at random, and send them your marketing page. Tell them you’re trying out this product idea and ask them for some feedback. Videofruit has a specific list of questions to ask, which I also used. When they reply with an answer to your questions, reply back with a thank you and ask them to pre-order at the price point that you’re testing. I used Gumroad to take preorders (more on them in a bit).

- Revise the marketing page based on what you learned. The survey responses you received will be gold. Go back and revise the marketing page with this feedback. If 5 or more (that is, 10%) of your 50 subscribers actually put in their credit card and hit “pre-order”, test a higher price point this time. If 5 people ordered at $200, test $300.

- Take another 50 newsletter subscribers, and try again. Repeat the process with another set of 50 newsletter subscribers. Again, your goal is for 10% of them to put in their credit cards and hit “preorder”.

Once you’ve got 10% of your test group preordering, you can start actually developing the product. Overall, this process took me about 4-5 months from the time of accepting preorders to actually shipping. In that time, I wrote ~125k words for the book, and produced about 6 hours of screencasts. After the launch, I’d produce another ~12 hours of screencasts which were “dripped” out after the launch.

Here are my product development tools and tips:

Don’t do DRM. This guide is for people developing infoproducts for programmers – don’t restrict their freedoms! Software developers hate DRM, so don’t do it. Your audience isn’t big enough that torrents or other illegal sharing could seriously affect your revenue potential, so why even bother? I looked at open-source licensing for the actual content of my course, but ended up deciding not to do it. Instead, all of the content of my course is DRM-free, distributed in several formats, and can be consumed with completely free software (i.e. no proprietary video codecs, etc).

I used Gitbook for producing the book itself. It’s really nice, because you can export to HTML, PDF, EPUB and MOBI and even JSON formats. However, styling Gitbook documents is waaaaay too difficult. I ended up just going with the default styles.

Sell a private Slack as part of your add-ons. I was surprised by how much value my readers got out of this, but it’s one of their favorite parts of the product.

Don’t write your own selling platform. I used Gumroad to take payment. It’s a solid checkout experience, and the fees they take aren’t too excessive. Sometimes people overseas do have problem with the underlying Paypal implementation, though, so if you’re selling mostly to non-US customers I’d look elsewhere.

Glue tools together with Zapier. I use several zaps that tie together Mailchimp, Gumroad, and Slack, for example. Once you purchase my product, you automatically get added to an email list and to Slack.

There’s no need for video to be super-high-polish. A lot of info-products produce extremely slick video content, but I think it’s unnecessary. I certainly didn’t go high-polish. I bought a $100 mic and $100 webcam and stopped there. Video is a time and money pit, and you can easily spend $10,000 trying to get your videos up to professional quality. Video content is also infinitely harder to keep up-to-date than text content. So be wary of video, and don’t spend too much time producing it.

The final product should have three tiers. The middle tier is the main product, the one you expect everyone to buy. Offer a slimmed-down version at a lower pricepoint, and then offer a bonus version with a higher pricepoint. My lower pricepoint was $99, my middle tier $200. My third tier was a “corporate package”, which I envisioned as a kind of training workshop for corporate clients. It turns out that none of them wanted that – everyone who emailed me about the “corporate package” was asking about per-seat pricing for the Guide itself, which I did not want to do. So, no one ended up actually purchasing my “third tier”.

Refunds are not a problem. In hundreds of sales, I’ve only had 4 refunds. Offer as many money-back, 100% satisfaction guarantees as you can on the selling page, because they provide far more benefit than cost.

Lessons Learned

If I could go back and do anything differently, I would say that I would make writing my habit rather than my job.

If you write 1,000 words a day, every day, that’s 365,000 words a year. Now, with practice, I’ve gotten to the point where writing 1,000 words takes me just about an hour. 365,000 words in a year is a huge output, though – enough to support a book plus at least a blog post per week.

However, I didn’t do that. Instead, I was completely crunching up against my self-imposed deadline and writing 3-5k words per day in the month before I launched the course. It was awful, and was a major factor in me feeling too burned out to continue blogging consistently after the course launched.

I think I could have easily increased my revenue off this product 50-100% if I had simply blogged consistently after the course had launched.

I learned that consistency is more important than effort. It’s important that you write 1,000 words a day, yes, but really an even better goal might have been 1 word per day, or to just sit in front of the fucking keyboard for an hour every day. The hardest part of writing is just writing anything at all – usually once I sat down and actually started writing, it was far, far easier.

Look at successful content creators – they’re all about consistent output. I find YouTubers inspiring for this purpose. Many of them churn out a video every week, sometimes even more.

However, like I said at the introduction, the other thing I’ve learned is that writing can completely change your career. I’ve doubled my hourly rate, and I now get tons of inbound, serious inquiries, without any outreach on my part. Also, the brilliance of making money while you sleep is that it allows you to take extended vacations. I don’t think I really worked at all this year between June and September – I spent the entire time driving a car through the Western U.S., looking for a new place to live with my partner (we ended up in New Mexico).

If you have any questions about writing about programming, or tips or experiences to share, or you’ve got a slow Ruby on Rails app: email me.